During my Master’s program last year, I discovered an amazing person who quickly became one of my favorite historical women. Let me tell you a bit about Christine de Pizan, one of the most popular French authors from the turn of the 14th century.

Becoming a Writer

When her beloved husband died in 1390, Christine was left as a young widow with three small children and a widowed mother of her own to take care of. After battling her husband’s creditors and debtors in the courts, as well as her own grief, Christine turned to writing, first as an emotional outlet and then as a career. Determined never to remarry, she supported herself and her family as an author. She even personally oversaw the production of her books.

Christine had received an unusually sophisticated education for a girl in medieval France. Her father was an Italian astrologer and physician who ‘did not have the opinion that a woman should not learn her letters’.[1] Her experiences with learning led her to declare that ‘the intellectual inferiority of women came from their education, or the lack of it. If it had been the custom to put little girls to school and teach them the sciences as was done with boys, they would have learnt it just as perfectly’.[2] How true! She herself had a typically male education, studying the liberal arts and Latin. Her strong education is evident in the sources she cited throughout her works. She quoted Cato, Dante, Boethius, Boccaccio, and more. Her books were full of references to ancient Greek and Roman mythology, astronomy, and contemporary literature.

A Prolific Author

Christine was a prolific writer, particularly in the early days of her career. Her earliest datable text is a ballad that dates from 1395 or 1396, and her first surviving manuscript was begun in 1399. Between that time and 1405, she wrote at least twenty distinct pieces, not including additional verses written for her anthologies. After 1406, the pace of her writing slowed as she focused more on editing and publishing her previous works.

Her active writing career ended in 1418, when she was forced to flee Paris in the wake of the civil war. She wrote a few more pieces between this time and her death in the early 1430s. Her last known composition was a poem praising Joan of Arc for her role in defending France. I particularly like that one, as it’s just the perfect combination of two incredibly strong women.

Helping Women

Two of her most famous works are the Cité des Dames (City of Ladies) and Le Livre de Trois Vertus (Book of Three Virtues). In both of these books, she focused on the positive impact of women in the world. She described an imaginary city in which were gathered the greatest women in history and literature. She taught her readers about their virtues and skills so that they, too, could help improve the world.

Her greatest desire was to see her books spread throughout the world. Queens, princesses, and women of all stations needed the skills and wisdom she described in order to function in society. (See her quote at the end of this post, for those who want to take a crack at medieval French.) Christine knew her works had value for the world at large, and she particularly wanted to transmit good books to women. She did not advocate that all women lead independent, scholarly lives as she herself did–she knew the value of motherhood and family–but she also knew the importance of education and basic literacy and numeracy for women as well as men. She wanted her books to make a difference and improve the lives of her contemporaries.

Book Production

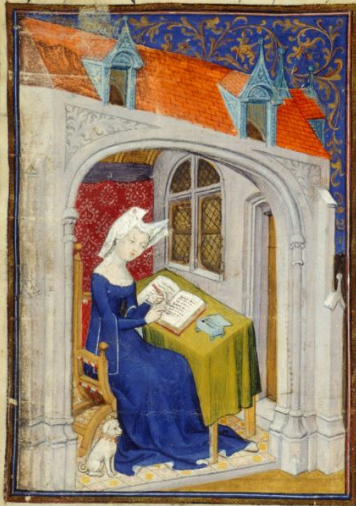

For me, even more incredible than her writing is the fact that she personally helped produce the physical books. The word ‘publisher’ is an anachronism, but Christine’s involvement in the material production of her books fits well within the parameters of what a modern publisher does. At the very least, Christine served as editor, modifying her text for each new edition. She also directly oversaw the various artisans and craftsmen who worked on her books. In one of her books, she praised the miniaturist Anastasia (basically a Medieval illustrator) and how her delicately-rendered illustrations were sought by book producers throughout Europe. (To me, this is a great example that women were much more involved in Medieval society and culture than we sometimes believe)

Christine may even have served as scribe herself; several of her references seem to indicate that. So we could very well be looking at her own handwriting when we see her original manuscripts! And the miniature paintings depicting herself are almost certainly accurate portraits.Today, some forty-five of Christine de Pizan’s works survive in fifty original manuscripts produced during her lifetime. Most if not all of these surviving contemporary manuscripts were produced under Christine’s personal supervision.

I loved learning all of this about Christine. I am still awed by her commitment to books, literature, and improving the lives of women.

If you want to see a beautifully digitized copy of one of her original manuscripts, check out the British Library’s manuscript viewer.

Footnotes

“Continuelment je le desire, me pensay que ceste noble oeuvre multiplieroye par le monde en pluseurs copies, quel qu’en fust le coust: seroit presentee en divers lieux a roynes, a princepces et haultes dames, afin que plus fust honouree et exaucee, si que elle en est digne, et que par elles peust estre semmee entre les autres femmes.” From Christine De Pizan, Le Livre Des Trois Vertus, ed. by Charity Cannon Willard, Bibliothèque Du XVe Siècle, L (Paris: Editions Champion, 1989) p. 225, ll. 12-17.

[1] Christine De Pizan, Christine de Pisan: Autobiography of a Medieval Woman (1363-1430) trans. and annotated by Anil De Silva-Vigier (London: Minerva Press, 1996) p. 210.

[2] Ibid.