The time has come to make a bit of a change in my blog posting. While I really enjoy crafting my long posts about various aspects of writing, I worry that I will burn myself out if I continue at this same weekly pace. So I’m going to try a new system, in which I post writing advice every other week. In the interim, I’ll post shorter pieces on other subjects related to books. We’ll see if it works!

For this week, I’d like to talk about the source of my header image. I’ll include a full copy of the image, broken in two due to size limitations:

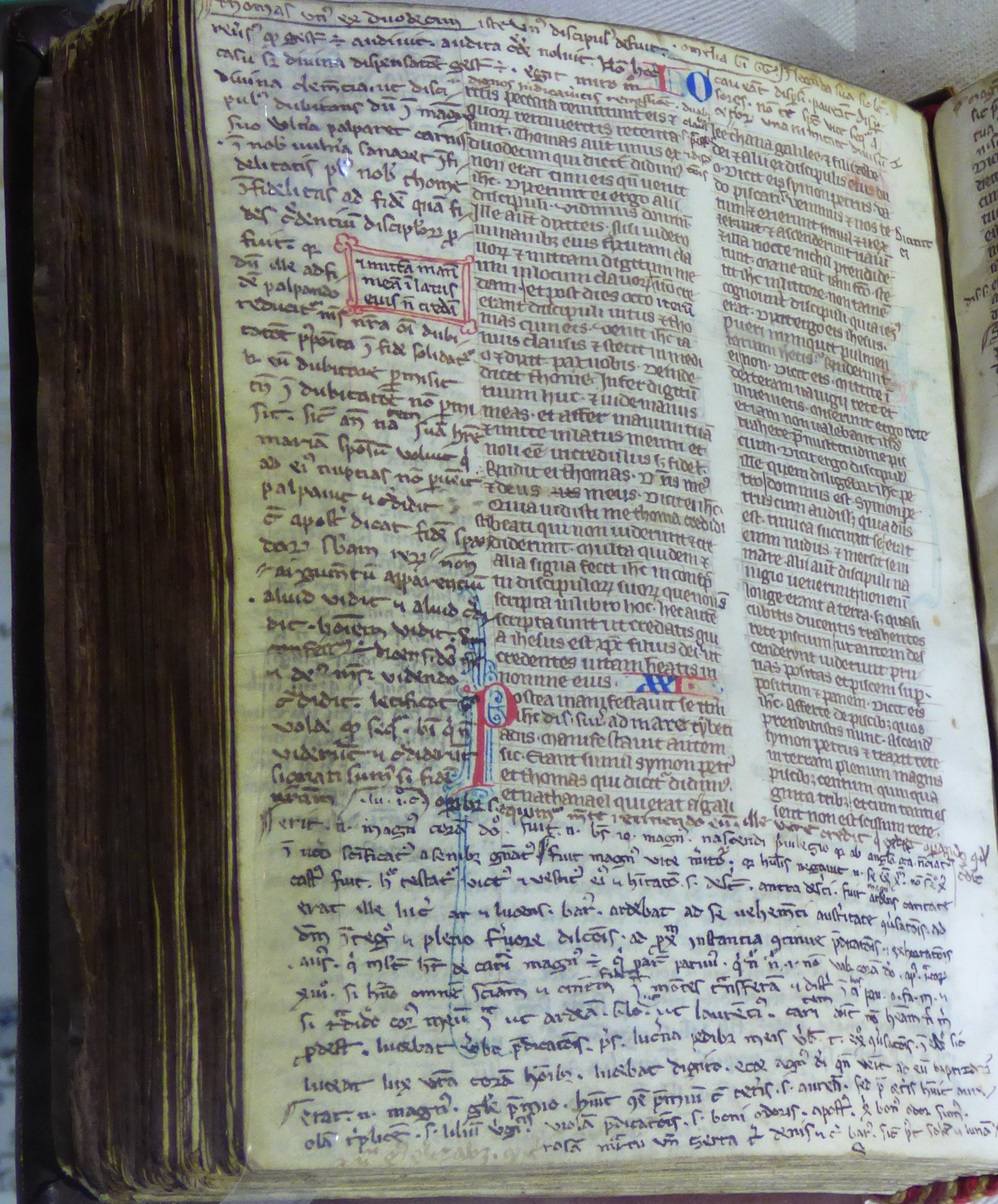

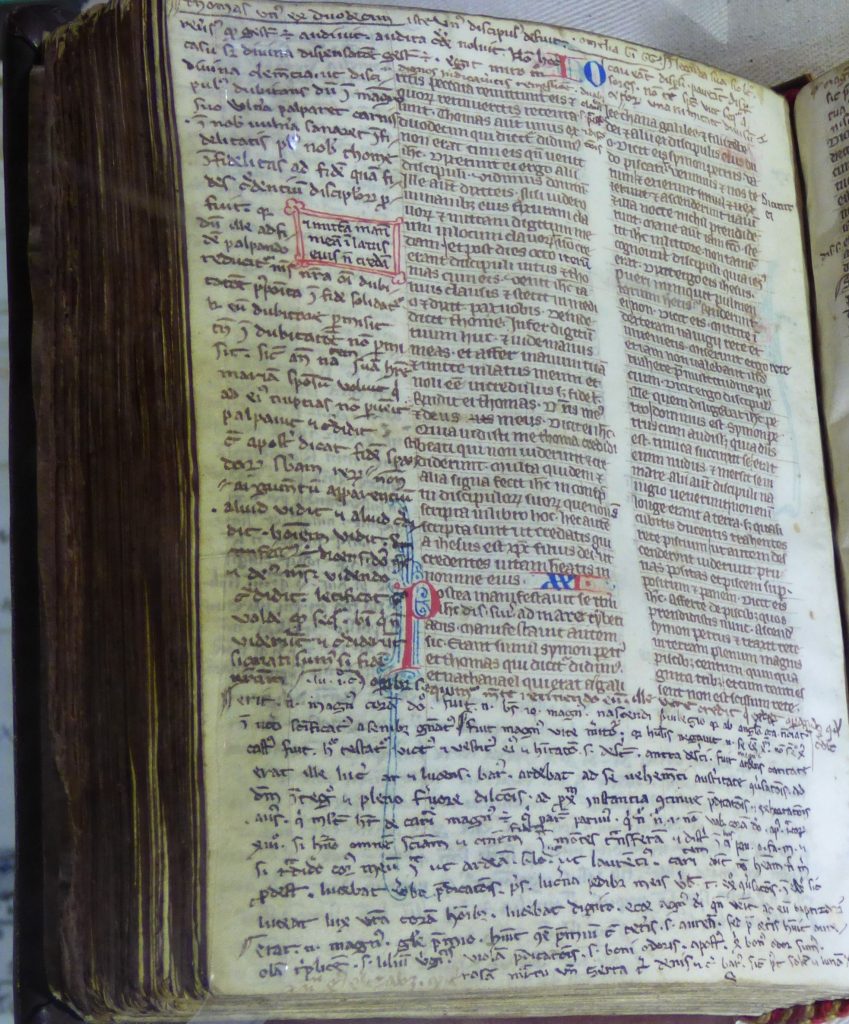

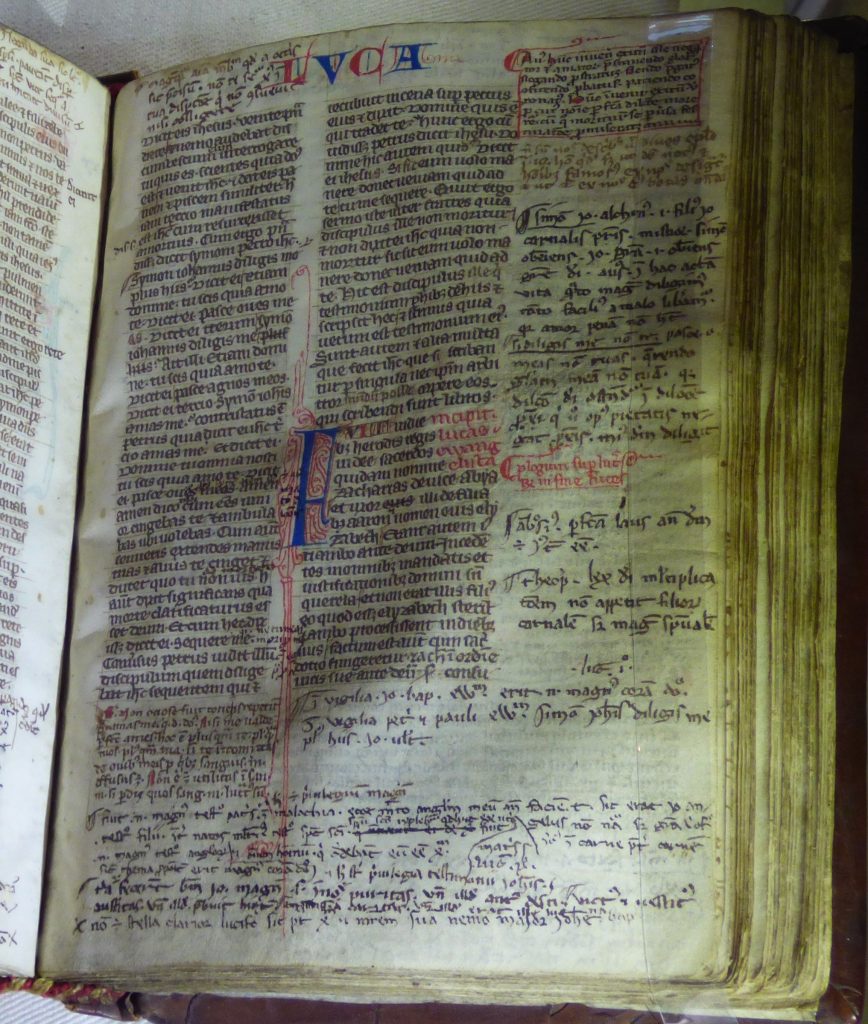

This is a picture I took of a page in a 13th century Bible. I had to write an essay about this particular type of Bible for my master’s program, so I’m going to give you just a bit of book history as context for the image.

Prior to the 13th century, Bibles were large, multi-volume affairs that tended to reside on pedestals and certainly weren’t easily transportable. But a variety of technological and cultural developments led to the production of what are now called “pocket Bibles” (though they weren’t by any means small enough to fit in a modern pocket). A lot of these developments are noticeable even in these two pages.

Technological Developments

By the 13th century, parchment makers had developed techniques to provide much thinner vellum, so more pages could fit in one binding. I was lucky enough to be able to handle this Bible and turn its pages. You can’t really tell this from the image, but I can attest that the pages of this bible were quite thin—very similar to the feel of Bible paper you might expect today. And yet, they were made from the skin of an animal, stretched and scraped to incredible thinness.

A more visible development is in the writing on the pages. Handwriting had developed to be more compact, and biblical scribes had taken to using an extensive array of abbreviations. If you look closely at the text in the four columns, you can see many examples of words with a straight line over a letter or two, like an underline but on top. Kind of like this: ĀĪ. Surprisingly difficult to recreate via typing. Anyway, this symbol indicates an abbreviation. You can also clearly see how compact the handwriting for the text is. Honestly, every time I look at a scribed book, I’m just so impressed at the handwriting of those scribes. The letters are so consistent, they almost look printed to me!

With thinner paper and smaller handwriting, much more text could be fit into a smaller book. Suddenly, it was possible to put the entire text of the Bible in portable form.

Cultural Developments

You’ll also note in this image the variety of not consistent handwriting in the margins of the text. This is what book scholars like to call “marginalia.” I don’t know who wrote the marginalia in this book, though it was certainly more than one writer. I can see at least two handwritings in the margin. The presence of marginalia in this pocket Bible provides a possible connection to two of the cultural developments that led to such portable Bibles: the development of universities and the preaching of friars.

Cambridge was founded in 1209, the University of Paris was founded in 1257, Oxford claims a foundation date of around 1096. These universities and others like them were focused primarily on ecclesiastical studies, and students needed Bibles to study. Much simpler to purchase a pocket Bible such as this to carry to class, instead of some weighty, two-volume set. Some have argued that the pocket Bibles weren’t conducive to studying, since their margins were so much smaller. But the presence of marginalia in this Bible (and many others) directly refutes that assertion. Of course, we can’t be certain that this book was used by a university student in the 13th century, but it is certainly possible.

The other most likely user of a book such as this is one of the travelling friars. The Order of Dominicans was a group of friars founded in 1216 for the purpose of extinguishing heresy. They traveled around Europe preaching the Gospel, and they relied on the authority of the Bible. The preceding centuries had seen efforts to standardize the biblical text, and most of these pocket Bibles contained the now-standard canon. Pocket Bibles were therefore perfect for friars to use in reclaiming heretics. Instructions for these friars often included an order to purchase a pocket Bible.

Whether scholars or teachers, the owners of this book clearly took their study of the scripture seriously!

From Bibles to Modern Books

A lot of the history of books can be traced through the history of the Bible. After all, Gutenberg’s most famous production was his printed Bible. Each development in the history of book production took humanity one step closer to the modern book-topia we have today. From pocket Bibles to increasing literacy to printed paperbacks and beyond, the evolution of the book is a fascinating thing. At least to me!

So there you have it, a bit of book history and some background on one of my images. I hope you found some bit of this interesting, and if not, well then, I’ll be back next week with more modern writing advice! Until then.