“Show, don’t tell” is a phrase that gets flung around a lot in writing and editing circles. I’ve seen people complain about it and even come to hate the phrase. Perhaps in part because it is used a lot. But I think a fair portion of the dislike of the phrase comes from frustration. It is very easy to say “show, don’t tell” but much harder to actually put the principle into practice. So what do editors (and writers) mean when they say “show, don’t tell”? And how, precisely, does one show instead of tell?

Showing vs. Telling

When you write, you are quite literally telling someone a story. So how are you supposed to not tell? Show-don’t-tell does not mean you rely on illustrations. The difference between telling and showing in written text is how much you spell things out for your readers and how much you let them deduce on their own. Wikipedia (because this is a blog post and I can cite Wikipedia if I want to) describes it as “avoid[ing] adjectives describing the author’s analysis, but instead describ[ing] the scene in such a way that the reader can draw his or her own conclusions.” Ironically, in fiction your job as the author is not to give the reader your own analysis. Your job is to facilitate your characters’ points of view. You don’t want to spoon-feed your reader.

If you write “Izzy was angry,” you’ve just told us your interpretation of how Izzy feels. The reader doesn’t have to figure it out. But if instead you write “Izzy glared at him, fists curled tight,” we get the idea that she is angry without you telling us. You’ve given the reader a chance to extrapolate—and you’ve provided a more vivid image, to boot.

That is the key to show-don’t-tell. You want to help your readers visualize your world. Again quoting Wikipedia, you want to “allow the reader to experience the story through action, words, thoughts, senses, and feelings rather than through the author’s exposition, summarization, and description.” Readers will remember and connect to an evocatively described scene more than a flat list of descriptive words.

So, how do you show?

How to Show

Say you’ve sent your manuscript to an editor (or a savvy friend) and they’ve written “show, don’t tell” all over it. What should you do? Here’s a quick step-by-step list for starters:

- Picture the scene in your mind and compare it to the words on the page.

- Look for actions or facial expressions or sensory details that haven’t made it into the text.

- Decide which of those aspects conveys the same message that you tried to get across by telling.

- Describe that instead!

Also look for ways that you can use your new description to serve multiple purposes. In describing a sad someone’s sorrowful eyes, you can also sneak in a hint about their eye color. When describing an angry character stomping away across the open plain, you can show us how his passage tramples the native grasses. The more you can turn your description into double duty writing, the better.

As with all of my writing advice, I’m not telling you never to “tell” (so, basically, I’m not Hemingway). You don’t want to go too far into the showing realm and end up with pages of description that the reader couldn’t care less about. Sometimes the scene calls for a short and sweet telling. The more you practice your craft, the more you will recognize opportunities for showing instead of telling.

When to Tell

One very clear example of when you can tell is in dialogue. Dialogue is often full of telling. Think about your own conversations. We say things like “James is annoyed with you” all the time. We’re not going to pause in our conversation, remember what James looked like, and say “James was creasing his forehead and rolled his eyes when I mentioned your name”—and expect our conversational partner to deduce that James is annoyed.

Telling in dialogue works because, by having the characters tell something, you’re actually showing us more about that character and their thought processes. An example:

What can we learn when Sarah says, “Be careful, Izzy, I think James is annoyed with you”?

- Sarah cares about Izzy, is observant enough to read James’ emotions on the situation, and has seen James more recently than Izzy has.

- Or, depending on the context, maybe Sarah is looking to cause trouble by making Izzy mad at James.

- Or maybe we learn that Sarah is completely oblivious because we as readers know that James is secretly in love with Izzy and he’s just frustrated that he hasn’t had the courage to tell her!

Sarah’s telling in this case is showing, particularly once you’ve set up the character relationships and the context of the scene.

Other times, the pacing or poetics of the scene may simply call for telling. You have to use your best judgment on when to show and when to tell so you can move on to more important things.

Show, Don’t Tell

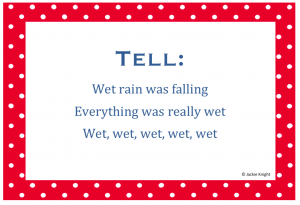

There you have it. I hope I have adequately told you when to show and showed you when to tell. And in case all this telling and showing has got you confused, I’ll leave you with this wonderfully telling haiku:

This is truly helpful!!!

I’m glad! And thank you for letting me know!

When the writer shows the story from the character’s perspective, hardly the readers will drop the book — they’re living with the character, the events are them as well. The readers see, listen, think and feel what the character lives. They have to interpret the meaning that you, the writer, print it.